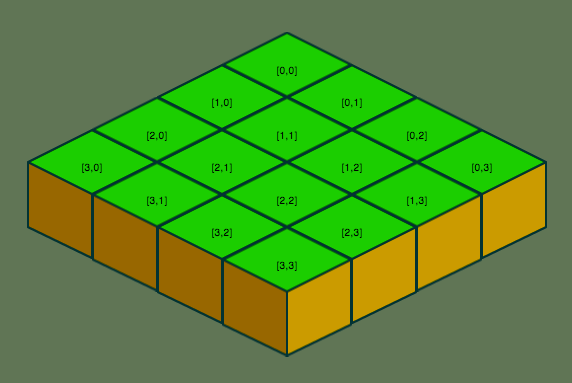

We have created an isometric world and a character that moves around in the world. But let’s say we want to add things in the world that the character can interact with. There may be an enemy on another tile, for example, and when the character encounters this enemy, the game would switch from a “map mode” (which is where we left off in my previous post) to a “battle mode” where the character must fight the enemy.

So let’s add an enemy model:

var EnemyModel = Backbone.Model.extend({ defaults: { x : 0, y : 0, row : 0, column : 0, destX : 0, destY : 0, destRow : 0, destColumn : 0 } });

And let’s add the enemy on tile (3,3) by editing MapView:

/** * Load enemy */ loadEnemy : function(context) { var img = new Image(), originTile = context.tileMap[3][3]; img.src = 'img/enemy.png'; $(img).load(function() { // create spritesheet and assign the associated data. var spriteSheet = new createjs.SpriteSheet({ //image to use images: [img], //width, height & registration point of each sprite frames: { width: 152, height: 156, regX: 0, regY: 0 } }); context.enemy = new createjs.BitmapAnimation(spriteSheet); context.enemy.x = originTile.get('x'); context.enemy.y = originTile.get('y'); context.enemyModel = new EnemyModel({x:context.enemy.x, y:context.enemy.y, row: originTile.get('row'), column: originTile.get('column') }); context.enemy.regX = 110; context.enemy.regY = 174; context.enemy.currentFrame = 0; context.stage.addChild(context.enemy); context.stage.update(); Main.init(); context.trigger('EVENT_MAP_LOADED'); }); }

Notice that it triggers the event “EVENT_MAP_LOADED” at the very end. I have made loadEnemy be the last thing loaded, after the world and after the player have been loaded, so that the game will be notified that everything in the world have been loaded. We will go over what happens when this gets triggered later.

Modify movePlayer() in MapView (see code in red):

... if ( (playerX === destX) && (playerY === destY) ) { //console.log('splice'); context.model.set('movePlayer', false); context.playerModel.set('row', destRow); context.playerModel.set('column', destColumn); context.playerModel.set('x', destX); context.playerModel.set('y', destY); if (context.path.length > 0) { context.path.splice(0,1); if (context.path.length > 0) { context.movePlayerToTile(context, context.path[0]); } else { context.model.set('movePlayer', false); if ( (context.playerModel.get('destRow') === context.enemyModel.get('row')) && (context.playerModel.get('destColumn') === context.enemyModel.get('column')) ) { context.trigger('EVENT_MAP_REACHED_ENEMY'); } } } else { context.model.set('movePlayer', false); if ( (context.playerModel.get('destRow') === context.enemyModel.get('row')) && (context.playerModel.get('destColumn') === context.enemyModel.get('column')) ) { context.trigger('EVENT_MAP_REACHED_ENEMY'); } } } ...

You will notice another event here, “EVENT_MAP_REACHED_ENEMY.” When the player and enemy are on the same tile, this event will be triggered. So what happens when this gets triggered, and when the other event, “EVENT_MAP_LOADED” gets triggered? Let’s go to our main file to find out. I’ve highlighted those parts in red, as well as some other parts that get affected.

var Main = (function($){ var mapModel = new MapModel(), mapView = new MapView( { model: mapModel } ), gameMode = 'MODE_MAP'; var init = function() { mapView.on('EVENT_MAP_LOADED', Main.onLoaded); mapView.on('EVENT_MAP_REACHED_ENEMY', Main.onReachedEnemy); }; var onLoaded = function() { Main.ticker(); }; var onReachedEnemy = function() { alert('BAAAAAHTTLE MODE!'); Main.gameMode = 'MODE_BATTLE'; }; var ticker = function() { createjs.Ticker.setFPS(40); createjs.Ticker.useRAF = true; createjs.Ticker.addListener(Main); // look for "tick" function in Main }; var tick = function(dt, paused) { switch(gameMode) { case 'MODE_MAP': if (mapModel.get('movePlayer') === true) { mapView.movePlayer(mapView); } break; case 'MODE_BATTLE': break; } mapView.stage.update(); }; return { gameMode : gameMode, init : init, onLoaded : onLoaded, onReachedEnemy : onReachedEnemy, ticker : ticker, tick : tick }; })(jQuery);

So, on “EVENT_MAP_LOADED,” we start the ticker for the game loop. “tick()” gets called every frame. In tick(), we have a switch case with different game modes. Initially, we are in “MODE_MAP,” which is the mode in which the character travels around in the isometric world. When the character reaches the enemy’s tile, “EVENT_MAP_REACHED_ENEMY” gets triggered, and we switch to “MODE_BATTLE.” At this point, the character is not able to move around in the world anymore, and we can switch to a different screen that can perhaps show the character’s hit points, skills, items, etc. for fighting the enemy. The interactivity at this point can be real-time combat or turn-based or a mixture of both… it’s up to you!

Of course, this concept can be followed when adding items to the world (reaching a tile with an item on it could trigger a prompt to pick up the item) or people (reaching a tile with a person on it could trigger dialogue), and we could have different game modes for each of these.

Ideally, we would want to make a state machine to handle the different game modes, and the different modes can be in a data structure, such as a stack. We could be in MODE_MAP when travelling around the world, and when we reach an enemy, push MODE_BATTLE to the stack, and when done, pop it off. Eventually, we could have many different modes, such as MODE_INVENTORY to manage your items or MODE_SETTINGS to update your game settings. But since we are in a “prototype” phase, we can go with this way for now.

Speaking of prototype, I may switch to another framework as I realize more and more of this game’s requirements for its production phase, such as mobile support. I may write about this more in my future blogs, so stay tuned.